Westminster Nurses on the Frontlines of COVID-19

James Stimpson, director of the Westminster Master of Science in Nurse Anesthesia program, on duty in New York

by Liz Dobbins (’21)

New York

It's your first day. You pull up to Coney Island Hospital along with 500 other nurses and see three refrigerated semi-trucks. The site seems mundane and unimportant so you let it pass. As you pull up to the front of the ER, a giant white tent contradicts the glimmering modern hospital. The bus stops and a sea of fresh-and-ready nurses deboard. A tired nurse in disheveled scrubs, stapled boot coverings, and a greatly worn mask greets you. They lead you first inside the triage tent, into the ER that is overrun with the sick, through a hallway lined with even more ill patients on stretchers, and into the ICU where, again, the room is filled to bursting with patients. This is what Westminster nurse and director of the Master of Science in Nurse Anesthesia program, James Stimpson, experienced during the beginning of his 21 days in New York in March, shortly after the global pandemic of COVID-19 hit.

“The things we saw would be like ‘This isn’t real,’” James says. “They had stretchers right next to each other with 70 patients on them. Some had COVID, some didn’t. Some would be there because they were pregnant and bleeding, and they would be right next to a COVID patient because there’s no room to put them anywhere. Everybody that came through the hospital had COVID—or got it before they left.”

The lack of space for patients—which was the state of every hospital in New York—resulted in every medical and hospital worker having a high likelihood of contracting COVID-19. Each day by the hundreds, hospital workers would call in sick leading to even less people to care for patients and manage operations.

“We had all these patients with a lot less providers than we had in the first place to take care of them,” James says. “You can imagine the quality of care was just horrible. That’s why you may hear some people talk about it being a war zone. I didn’t understand what that meant before I got there, but it was because people were literally dying because nobody could take care of them.”

With the numbers of nurses dwindling fast, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo sent out a plea of help to nurses in every state that was better off than New York. James answered the call and was one of 500 nurses sent to help. James’s experience on the front lines of the COVID-19 battle was something he, even having been in the Air Force, described as an experience he had never had. He worked over 100 hours a week for 21 days in the ICU trying to help patients fight for their lives—a fight that was often lost.

On any given day, James had three patients. While he was involved with studies—including transfusing blood from people who recovered from COVID to people who still had COVID—James’s primary role was taking care of the patients.

“Throughout the day my job would be keeping them alive,” he says. “Because these patients need time, right? They need time to heal from this virus. Meanwhile, that virus is just so detrimental. It’s taking over their cardiovascular system. Everybody that I took care of had COVID, everybody was super sick and many of them just didn’t survive.”

The lack of healthcare providers—along with the lack in supplies—only added to the detrimental experiences of those with the coronavirus looking for care. And it wasn’t just medication and ventilators that they were running out of.

“There are shortages of everything: Syringes, alcohol pads, medications, cups, needles, blankets, garbage bags. Every day, it’s something new,” James says. “We would run out of pads on the defibrillator that you need to shock people. If their heart went into a bad rhythm, we would know what to do, but we couldn’t do it because we didn’t have equipment. The hospital ran out of oxygen one night, so we had to ration that. We didn’t have blankets to put on the patients. We would have to get several gowns to put on them to try to keep them warm.”

Not only were they running out of everything imaginable, but they were also running out of beds due to the dramatic influx of patients everyday. And when somebody died, they had to free up that bed space quickly.

“When somebody died, sometimes they would be there for a little while until we could take care of them,” James says. “One thing that I was told was we have to take care of the living before we can take care of the dead, which means get them prepared to go to the morgue. But that was certainly a priority because that person was in a bed space that we needed. So we had to get them out as soon as we could.”

In a non-pandemic world, when a patient dies they are transported to the morgue. However, where James was working, each of the patients that had passed were taken to a refrigerated semi-truck—where they would stay for a month—so they could be quarantined before going to the morgue or a funeral home.

Three semi-trucks outside of Coney Island Hospital

"By the time I left, there were three giant semi-trailers out there,” James says.

The horror-movie-like experience James was having was not something easy to deal with and a lot of his fellow nurses that flew to New York with him quit after the first day. James credits his ability to continue the fight to two things: his ability to compartmentalize and his military training.

“Being in nursing, you have to be that way,” he says. “If you have a patient that has a bad outcome, you can’t hang your head and worry about it because the next patient deserves 100 percent. You have to be able to cope with that quickly and move on. You had to be flexible through all of this. You had to be able to understand that you don’t have all the information and you are expected to do things without the proper supplies and training. That is exactly how the military works: quitting is not an option.”

So James did not quit. He stayed in New York for 21 days, worked over 300 hours with no days off, and came out the other side with an entirely different perspective.

“The benefit for me was it was three weeks. I know I can do anything for three weeks,” he says. “It was easier to deal with. But morale is definitely low in New York.”

Despite this, James says that we are moving in the right direction. “There is hope,” he says. “Trends are showing that we are getting on top of this. Hopefully we can keep going in that direction.”

One of the ways he recommends moving in the right direction is changing our habits here, even if we are over 2,000 miles away from the US epicenter of the pandemic.

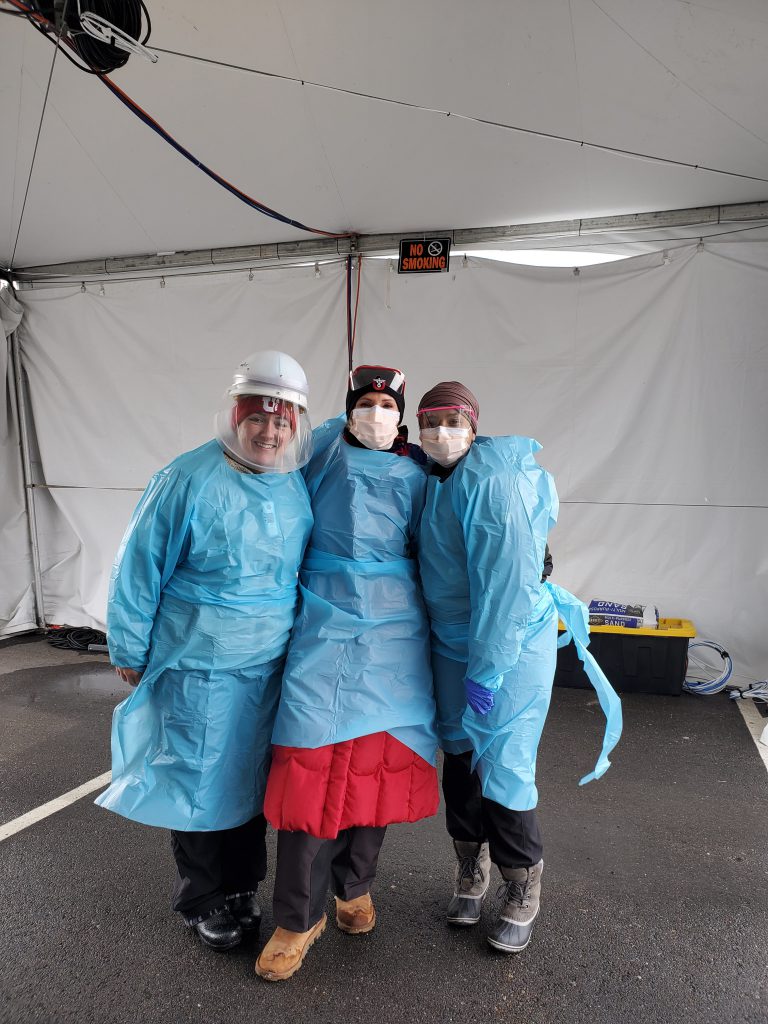

Westminster Master of Science in Nursing-Family Nurse Practitioner student, Brooke Bunkall (’18, MSN-FNP ’21) left, with two other Utah nurses in a COVID-19 testing tent

Utah

On the home front, Westminster nurses are also doing their part to help contain the coronavirus. Nursing graduate and Master of Science in Nursing-Family Nurse Practitioner (MSN-FNP) student, Brooke Bunkall (’18, MSN-FNP ’21), is currently working in an urgent-care clinic for University of Utah Health. In March she became one of the first nurses in Utah to begin administering tests for COVID-19.

“Before the testing sites, people would come to urgent care. We’d have to put on all of our personal protective equipment (PPE) and go test people out in their car,” Brooke says. “It was hard because we were super busy in the clinic. It was hard to manage being the only nurse testing and running an urgent care. It was very chaotic at first and there weren’t a lot of protocols in place. Then it became a bigger issue, and they opened up the tent testing sites, which became a lot more fluid and less chaotic. It runs like a well-oiled machine.”

Now, there are dozens of testing sites and tents across Utah and in Salt Lake, and Brooke’s job has slightly changed. She is now responsible for caring for non-high-risk COVID-19 patients, taking care of those who come in with typical injuries, calling with results for hundreds who have been tested every day, and trying to keep the ER and ICU from being overrun with patients.

Utah nurses have also been preparing and learning from what is going on in New York. Specifically, they are being conscious of how much PPE they use a day. “We are limited to one surgical mask a day, whereas before we changed it multiple times a day,” she says, also commenting on their plan to UV sterilize old gear rather than just throwing it out.

Like many others during these times, Brooke has a lot of anxiety surrounding the unknowns. To help with that she stays away from the news on her days off and has zoom calls with her friends. She also checks her anxiety by reminding herself that COVID-19 is a virus, and she needs to take precautions like she would for any other virus.

“I’m not going to necessarily treat the coronavirus any differently as far as I’ve always washed my hands; I’ve always worn masks during flu season,” she says. “I’m a little bit more heightened of what I do as far as where I set my mask down or how much I’m washing my hands.”

However, Brooke also realizes the difference between this virus compared to others like the flu. And since she first saw the news of the coronavirus, her perspective has changed. “When I first heard of it, I didn’t know how quickly and when it would reach the US and how widespread it was becoming and how sick people were getting,” Brooke says. “It made me realize how quickly something can spread even though it’s in another country. I don’t think people truly realize how quickly things can spread. I didn’t either. Even as a nurse.”

As the pandemic crept from country-to-country, jumped oceans, and put a black mark across the globe, nobody was prepared. Expectations in the early days of how deadly this would be were set very low. Now, all that’s left for us to do is think locally and try to flatten the curve the only way we can: through social distancing, hand-washing, and mask-wearing—simple precautions that save lives.

Protecting Utah’s Communities: Takeaway Thoughts

While many may not be able to fight this pandemic on the frontlines like James and Brooke, everyone has a part they can do. According to the CDC and our Westminster nurses, there are six steps everyone can do daily that will save lives:

- Stay home when you can

- Wash your hands often

- Keep at least six feet of space between you and others.

- Keep away from people who are sick.

- Clean and disinfect commonly touched objects.

- Call your healthcare provider if you feel sick or have concerns about COVID-19.

Resources:

- Proper hand washing videos: cdc.gov/handwashing/videos.html

- CDC stress-coping recommendations: https://www.cdc.gov/mentalhealth/cope-with-stress/

- Westminster COVID-19 updates

About the Westminster Review

The Westminster Review is Westminster University’s bi-annual alumni magazine that is distributed to alumni and community members. Each issue aims to keep alumni updated on campus current events and highlights the accomplishments of current students, professors, and Westminster alum.

GET THE REVIEW IN PRINT STAY IN TOUCH SUBMIT YOUR STORY IDEA READ MORE WESTMINSTER STORIES